Ronnie Goodall (COL ‘84) On the Importance of Interpersonal Connection, the Courage to Try, and Community Engagement

Posted in Announcements Blog Fitness Fitness & Wellness Corner News Racquet Sports Staff Profiles

Emma Chuck (C’22)

Campus Recreation Communications Assistant

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The facts of Ronnie Goodall’s (COL ‘84) tennis career are clearly impressive: he was a nationally ranked tennis player, garnered the NAACP Athlete of the Year during his time at Georgetown University, and served for a decade as Senior Manager for the United States Tennis Association’s Mid-Atlantic section. However, just a single conversation with Goodall reveals the depth of his commitment to helping other people, his diverse professional experience, and his ability to thoughtfully reflect on it all. Through uncertainty and obstacles, Goodall shares how he has embraced the unexpected and keeps surging on, always in search of improvement.

His journey to tennis began, ironically, with roller derby, a popular activity for him and his friends during the mid-70s. In the short period of time that native Washingtonian Goodall lived in Maryland, he and his friends frequented the tennis courts for their own purposes. He said, grinning, “It was one tennis court. It was surrounded by a fence that my friends and I could do the roller derby, around the tennis net, and bump each other into the fence so we wouldn’t have to go out of bounds. Then one guy came down to the tennis court. He wanted to use it, and he said, ‘Do you guys think you would rather play tennis on this court or keep skating? If you’re interested in playing tennis, I could teach you.’ And that’s how it all got started. I asked my grandmother for a racquet, and then it went from there.”

Goodall continued playing tennis because of the treasured friendships, a recurring theme in his life. He and his friends leapt into the competition and energy of the sport: “Whatever the group wanted to do, we just had a passion for it. And we’d like coming down to the tennis court and playing each other, and it was like some friendly competition to see who was the best this week and next week and the following weeks.” Though he initially engaged with the sport because of his connection with others, Goodall eventually found a passion for the sport individually, leaving the community court for more sites where he grew with the challenge of playing more advanced tennis players.

In his high school days, he found more people who shaped his tennis experience as well, shaping his life just as the man that initially and unexpectedly introduced him to the sport. Besides his coach, who was “my German history teacher,” Goodall shares an endearing story of “one lady that wasn’t a coach, she was a mentor,” who took it upon herself to support Goodall’s tennis career. He says, “She would help me take me around to the tournaments and let me know what tournaments I could play and should play. And then she took me on my first couple of college visits. She helped me out with things I might have needed for tennis.” Buying a tennis racquet, for example, was an understated yet crucial contribution that she performed. Though Goodall’s parents were fine with him playing, the extent of the financial expenses was less cause for enthusiasm, but his mentor stepped in to help meet his needs, thus cementing a significant role in Goodall’s life.

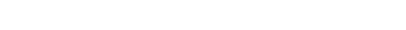

The spirit for continual improvement with others never left. When Goodall arrived at Georgetown University, he enjoyed a new realm of tennis life, where he had the chance to enjoy traveling and even being in the Big East Tournament. Goodall also praises Coach Rich Bausch, who “was a mentor. He really liked the sport, he wanted to see us progress, and we could really tell that.” Speaking of his time on the university team, Goodall summarizes, “We had a great coach, we had great practices… Bonding with the players, meeting other players of Michigan, New York.”

As for academics, Goodall’s trajectory was not so direct: though he thought he wanted to major in business, “I wasn’t really clear,” and he started working toward a degree in sociology instead. Confusion ensued when the option to start a transfer to the business program entailed catching up to the sophomore class and going to summer school to take business courses—difficult to do in conjunction with Goodall’s tennis tournaments and traveling. Eventually, though, he found his footing.

“I got into banking because I went to a job fair,” he says, and “I really liked the people that were there at the table, they were very informative. I knew I wanted to be in some kind of business background. I think they might have been the first people to call me back, and I was really excited that I could, you know, be in a field that I thought I would like.”

“…You want to work, but you want to work in a field or for an organization that you appreciate, and that you have respect for, and that you like.”

However, Goodall soon left banking for a new field. The reason for his transition was due to yearning to find something that he missed: “I always liked relationships with people, the customer service field,” that he previously had during his first job post-college as a Kmart manager. He found a new passion—in real estate.

The job was facilitated again because of “one of my tennis friends,” he says. “I was playing tennis and he was into real estate. But before that, when my mother sold her house, I got to go out with her. She wanted me to go looking at the houses with her.” He then realized that “going up to look at those houses with my mother and seeing how professional the registered real estate agent was, and doing everything that my mother needed to make sure that she was happy, I thought that was something that I wanted to get into.” He adds, laughing, “And they made decent commission checks.”

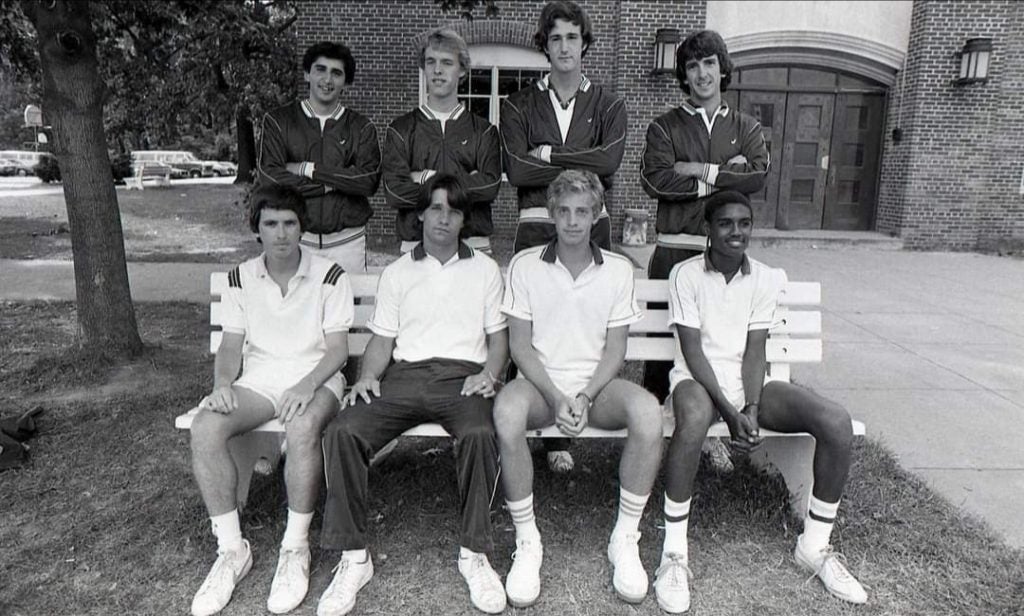

Goodall enjoyed real estate, but he truly found where he wished to be professionally, finally uniting his love for tennis with a drive to share it with others. The reason for the last and most lasting transition, he says, was due to two major reasons. “When I had my first child in 2002, I wanted her, when she got of age, to play tennis. So she played, and around six, I was putting her into these different tennis organizations and having to go to her afternoon classes and starting to play these little league tournaments and things like that, that’s when I wanted to get back into the administrative field of tennis. And so by her being in and me going to her matches, going to all of her practices, and seeing all the people, what was needed for her to be in these camps and different things like that, I started wanting to get back into tennis.”

The year his daughter turned six was 2008, when “you saw the market for real estate just crash. The revenue and income wasn’t coming in,” Goodall says, “So I was like, I better get a regular job. You want to work, but you want to work in a field or for an organization that you appreciate, and that you have respect for, and that you like.”

“The US Tennis Association (USTA) was one of the biggest organizations in the world. It had a really good name, and I loved their mission. And I knew what I could do, if I worked with that organization, so the combination of my daughter coming of age to play more tennis, to the real estate market crashing, and my love for tennis, it all came together that that was the right place for me to be at.”

“I want you to play it because you want to play it. If you want to play it just for fun, fine. If you want to play it [because] you want to be the best tennis player that you could possibly be, that’s fine also. I’m going to push it as far as you want to be pushed, but I want my players and the people I teach [to] know that I really care about them.”

With the USTA, Goodall was able to make true his dream of being on the administrative side of tennis programs and doing school outreach to bring kids and tennis together. Continuing his love for customer service and meeting people, Goodall was able to help implement tennis in schools’ P.E. curriculum and after-school programs. The job even allowed him to continue his love for traveling; Goodall was in charge of the entire Mid-Atlantic section. “I had to do outreach programs in West Virginia; Richmond, Virginia; all over. Traveling and meeting all these different people, all these different kids. Each time, I got a thrill.”

The job also came with a special perk: “Each year, we had annual meetings, and we would go to New York City and for the US Open. Nothing like being at the US open,” he shared. “That was a real fantastic thing. I was with the US Tennis Association for 10 years. But one of the biggest highlights, other than me doing my job and working throughout the section, was going to the US Open.”

Working with the USTA also allowed Goodall to pursue teaching, putting him directly in a position to engage with kids and create successful, impactful programs. One particular moment stands out: “The US Tennis Association has a team, a youth team tennis program, which is called Junior Team Tennis. So kids that I, I wouldn’t say raised, but worked with, from when they were eight, nine years old, they got to a level that we played 18 and under.”

They entered the local championship. When they were in the section championship, though, “I remember our players playing hard, and we played some big competition. We were down in Virginia Beach. And a memorable moment was when we had a match that we had to win so we could go forward. . . The mixed doubles was crucial because that was the last match, but one of the one of my players, a young lady, said, ‘Coach, I can’t. Her partner was very critical of her playing and dominated on court. And she’s like, ‘I can’t play like that, with this guy criticizing me.’

There was this other kid who stepped up. He’s like, ‘Coach I got this. Let me work with her.’ And he was very caring. He supported her on court. And when he came up, he put his arms around her, and he said, ‘Look, I got you, I’ll take care of you,’ they went out, and we played our toughest team. And [our] guys won. They won the match.” He continues, “Then I remember running out to the court, jumping up and down, like we’d won the NCAA. Like it was 1984, when Georgetown won the championship. People were looking at me. Why is he jumping up and down? But it was just so important. It was more than about winning, it was how they came together. These friends, these kids that grew up from eight, nine years old and [then] when they were 17, that they came together like this, with this common cause, their friendship, and how they thought and put everything together was just amazing for me.” (The sectional championship led to a trip to nationals, where they placed fourth. The trip allowed Goodall the opportunity to “[live] my life through them. I remember my teen years when we would travel. I was just living it through those guys, so it was a lot of fun.”)

The emphasis on experience and enjoyment has affected his teaching style. In his own experiences, his coaches “that pushed you hard” and stressed “you have to do better, you have to win your matches” did not work as well as coaches who “really cared about me as a person.” Therefore, in his own approach to instruction, Goodall says his philosophy follows his own easy-going personality: “I want you to play it because you want to play it. If you want to play it just for fun, fine. If you want to play it [because] you want to be the best tennis player that you could possibly be, that’s fine also. I’m going to push it as far as you want to be pushed, but I want my players and the people I teach [to] know that I really care about them.”

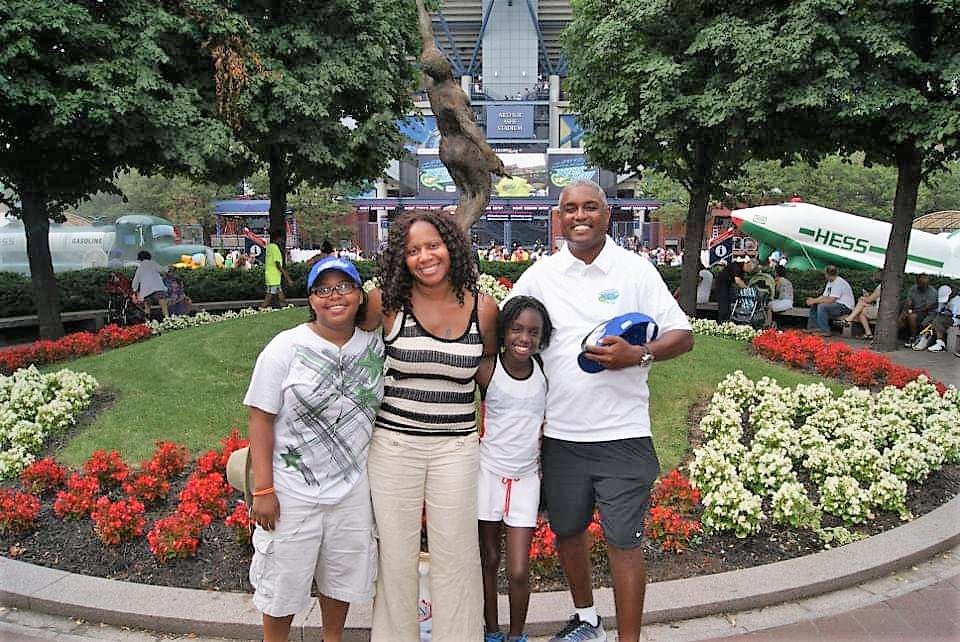

Now, Goodall works with the Washington Tennis and Education Foundation and manages the Arthur Ashe Children’s Program, where he oversees outreach programs. Though he rarely has time for physical coaching, he tackles his new challenges, a mass of new projects. He comments on the surprising uptick in tennis involvement in the latest year: “You would think, during this pandemic, things would have slowed down, but tennis is booming… We have a for-profit side, and we have a non-profit side. The for-profit side, where I work and manage the program, up at Rock Creek Tennis Center, where they have the Citi Open tennis tournament, we have a program up there that we’ve had our highest numbers, participation and revenue, for the past year, higher than ever.”

“Then my school outreach programming on the nonprofit side, with COVID protocols, we would normally be at schools after school, but the schools are not open. They did start going back, but they said they would only have a hybrid situation, but no physical after-school tennis programming. So we have a couple of sites where we had the kids, and the parents bring their kids to us, to do outdoor tennis. But because of the protocol and the capacity levels, we can’t have as many kids that we are used to having on the tennis court. But we are at capacity with that also.”

“We have three sites that were outdoors and I was like, I don’t know, the parents might not bring their kids when we first started, you know back in September and the parents are begging us to have after school programming outside. So we’ll wear our masks, and then we do our temperature checks, and all that kind of stuff. And the parents, the kids to be outside just running around hitting the ball over there, they don’t care if the ball went over the net or where it went, they were just outside doing something. And they got to see their friends. And then the parents were out there, watching their kids you know at a safe distance, socially distanced, they were watching their kids outside enjoying themselves rather than being in front of the computer doing virtual classes.

So that was another thing that made me really happy that you know we could do that for people. I’m always service-oriented, and, again, I always like feeling like I did a job well done.”

For the future, Goodall is planning an entirely new program of his creation. The AACP has an introductory program for tennis, but Goodall wants to take the program a step further. “We have some kids that I think could be really good tennis players, and I know that their parents want them to be more advanced and play the game at an advanced level. I’m going to work with a couple of coaches, and this is the part where I might get back on the court, work with them to develop the Arthur Ashe Children’s Program Tennis Team. I want them to travel, want us to play other organizations, but I want to get their games to the next level.” He hopes the team will spark a long-term interest in the sport. Goodall’s interest in sharing his own transformative experience with tennis throughout his adolescence is strong.

“It’s the perseverance, it’s that will, that, look, no matter how far you’re down, it’s how you get back up and how you continue. No matter what, if you lose, you lose. But out of every loss, just make sure you learn something from the losses.”

Though his time on the court himself is limited professionally, he says he has to “make it a point to get back out on the court at least once or twice a week. Especially working at home, it’s almost 24/7.” Though he defends that “it’s nice to have a job that you love, and you have a passion for, but you gotta have some quality time for yourself and step away from it for a little bit and do the things that you want to do. And tennis is something I want to do and play.”

Tennis is a guiding force in Goodall’s life, and he shares how the game has shaped his life: “It’s the perseverance, it’s that will, that, look, no matter how far you’re down, it’s how you get back up and how you continue. No matter what, if you lose, you lose. But out of every loss, just make sure you learn something from the losses.” For Goodall, his approach to life, inspired by tennis, follows this simple trifecta: “the will to win, the will to go on, and the will not to give up.”